Beyond Absurdity

How does one respond to people who speak as if stricken by some sort of amnesia?

Welcome, New Subscribers!

Since my most recent subscriber-appreciation message about a month ago, the number of subscribers to MISM has nearly doubled. In part, the increase reflects the law of small numbers, but I also attribute it to the incalculable increase in the level of engagement on Notes and through Chat.

I’m thrilled to welcome new subscribers, including

, , , , , , , , , , . (I did not neglect to include Frank Blaskovich but, for some reason, I can’t tag his profile.) I am grateful for your interest in my work and your decision to allocate a portion of your attention to MISM, a Substack dedicated to understanding media.Among the new subscribers, there's a communications professor, an anthropologist, a traveling glass maker, an R&D engineer, a palliative care physician, and an “onto-solutionist”. I love the diversity of my Substack subscribers. Sadly, I don’t have any information about most of the new subscribers who only use Notes without publishing their own Substacks. I welcome opportunities to get to know my subscribers better. Before the end of the year, I’d like to conduct a brief subscriber survey; in the meantime, please feel free to leave a comment below to let me know what brought you to Substack and to MISM.

In this post, I offer you my reflections inspired by the first two chapters of Marshall McLuhan’s From Cliche to Archetype. This is the second edition of an essay originally published on DaaS, which is now paywalled. If you’d like to explore any of the themes of my work through dialogue, please start by subscribing to DaaS for free and stay tuned for a special offer next week.

Beyond Absurdity: How does one respond to people who speak as if stricken by some sort of amnesia?

The first chapter of Marshall McLuhan’s From Cliche to Archetype focuses on Eugene Ionesco's first play, The Bald Soprano. At the start of the chapter, we find a quote about the play from Loss of the Self in Modern Literature and Art by Wylie Sypher:

Ionesco wrote his first drama in 1948, The Bald Soprano, as a tragedy of language, using the stereotyped dialogues he found in the Assimil-method1 primer from which he was learning English. As he studied the cliches in the exercise book — “There are seven days in the week, it costs too much, I don’t have the right change, the room is too warm, where is the W.C. — he felt the text changing under his eyes: it began to ferment, he says, and he saw that these automatic colloquies represented very well the collapse of our daily lives. We go on speaking as if we were stricken by some sort of amnesia. So, Ionesco wrote his anti-play in which the Smiths and the Martins talk, talk, talk the babble that sounds, when one is really able to really hear it, appallingly like what one hears at any cocktail party. The characters disintegrate into the jargon that serves us as a way of life.

Like the fish oblivious to the water they inhabit, participants in this way of life do not notice the automaticity of their daily interactions. They don’t notice their own dissolution into their jargon. They simply run their scripts.

In the first chapter of Loss of Self (‘The New Man as Functionary’), Sypher suggests that these scripts are not only self-evidently absurd but also “collectivist”:

We do not have to read contemporary literature to know that we are living in an age of togetherness, that Americans have accepted their own special kind of collectivism as it appears in the life of the organization man, whose existence is a mode of conforming to large enterprise. It would seem that individualism has been abandoned on both sides of the iron curtain.

Indeed, Sypher’s book is about the loss of self in modern literature, but as many authors have observed, great literature reveals truth without the use of facts.

Sniffing the Problem

When stars align, art, philosophy and science can jolt people out of the somnambulism that results from the loss of self. In Ionesco’s plays, for example, McLuhan sees “the unconscious brought up to daylight inspection.” He writes:

Pascal, in the seventeenth century, tells us that the heart has many reasons of which the head knows nothing. The Theater of the Absurd is essentially a communicating to the head of some of the silent languages of the heart which in two or three hundred years it had tried to forget all about. In the seventeenth-century world, the languages of the heart were pushed down into the unconscious by the dominant print cliche. In the contemporary world the unconscious is being retrieved and brought up into daylight awareness. This is done in both private and corporate psyche. Edward T. Hall in The Silent Language reveals many of the nonverbal gestures by which whole cultures communicate. He tells us, for example, that an eight-inch interval between speakers is normal and friendly in the Arab world. Beyond eight inches it is not easy to smell one’s interlocutor. When the Arab can no longer smell his interlocutor, he stops talking and begins gesticulating. A rather similar incident occurs in The Bald Soprano when the Smiths and the Browns, in the midst of a painful English silence, meet each other for the first time. The dialogue goes: “Sniff … sniff … sniff … sniff … sniff…”

These days, we rarely get to sniff our interlocutors, but even without this pheromonal data, we can sense that “the Western mind is changing its mind,” and this sensation induces a “metaphysical shudder”, an “absurdist frisson”.

Ionesco particularly cultivates the art of the verbal cliche, and he uses the verbal cliche to probe one of the most fascinating phenomena of our age and that is the way in which the Western mind is changing its mind. His characteristic effect is a sort of shudder, or frisson, not unlike the metaphysical shudder which George Williamson detected in much seventeenth-century metaphysical verse. It is probable that the metaphysical shudder was related to the shift from oral to written, and it is likely that the absurdist frisson is a seismic recorder of a global shudder from new environmental technologies. The extremely mobile individual consciousness of the print-oriented man now reverses into the tribal inertia of multi-consciousness. It is rather similar to what happens when countries demobilize at the end of a major war.

The Abyss Opens Suddenly

Next, McLuhan quotes Friedrich Durrenmatt’s Problems of the Theatre to explain why The Theater of the Absurd is called ‘tragic farce’.

Tragedy presupposes guilt, despair, moderation, lucidity, vision, a sense of responsibility. In the Punch-and-Judy show of our century, in this backsliding of the white race, there are no more guilty and also, no responsible men. It is always, “We couldn’t help it” and “We didn’t really want that to happen.” And indeed, things happen without anyone in particular being responsible for them. Everything is dragged along and everyone gets caught somewhere in the sweep of events. We are all collectively guilty, collectively bogged down in the sins of our fathers and of our forefathers. We are the offspring of children. That is our misfortune, but not our guilt: guilt can exist only as a personal achievement, as a religious deed. Comedy alone is suitable for us. Our world has led us to the grotesque as well as the atom bomb, and so it is a world like that of Hieronymus Bosch whose apocalyptic paintings are also grotesque. But the grotesque is only a way of expressing in a tangible manner, of making us perceive physically the paradoxical, the form of the unformed, the face of a world without face; and just as in our thinking today we seem to be unable to do without the concept of the paradox, so also in art, and in our world which at times seems still to exist only because the atom bomb exists: out of fear of the bomb.

But the tragic is still possible even if pure tragedy is not. We can achieve the tragic out of comedy. We can bring it forth as a frightening moment, as an abyss that opens suddenly; indeed, many of Shakespeare's tragedies are already really comedies out of which the tragic arises.

Secrets of the Garden

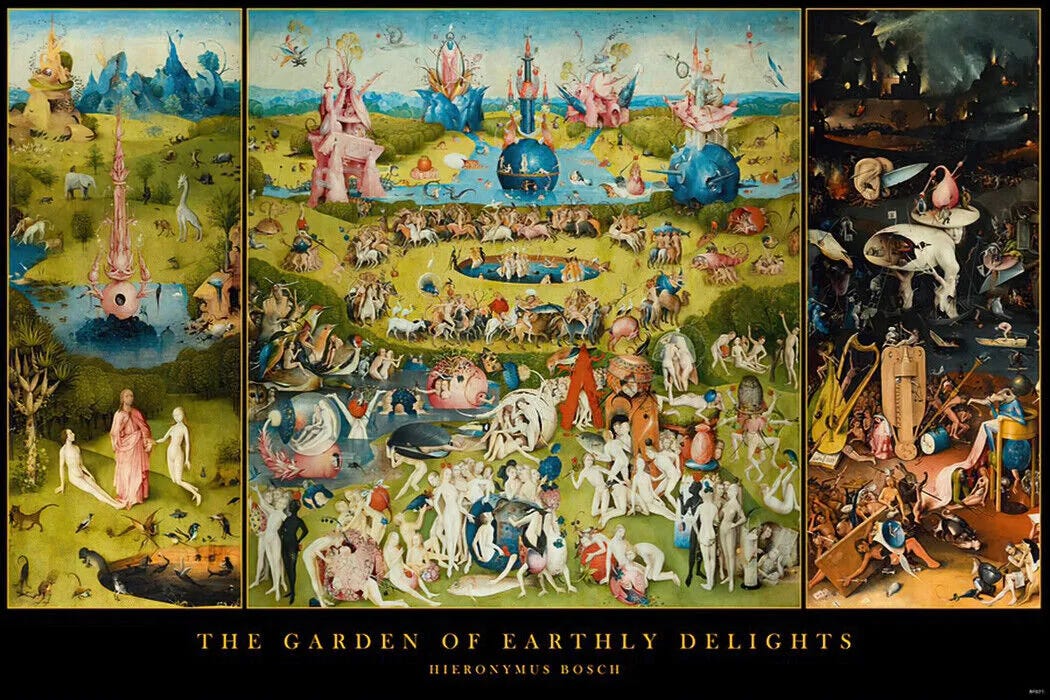

What’s grotesque about Hieronymus Bosch’s paintings? And where’s the comedy? As an example, consider the Garden of Earthly Delights, one of his triptychs. An initial glance at the exterior and interior panels might simply elicit a reaction along the lines of TMI or WTF.

But study the panels closely, as I did with the help of this introduction by the Creative Codex, and the initial shock deepens as the grotesque details come into view, with tragic and farcical effect:

A nude man being seduced by a pig dressed as a nun

A man shoving a bouquet of flowers into another man’s butt

An enormous bird feeding berries to a crowd of people

A man being skewered on the strings of a harp

A knight being eaten alive by giant rat-like creatures

A lizard with three snake heads

A man drowning himself in a pool of water while balancing a giant red fruit on his perineum

Amazingly, Bosch painted The Garden around the time when Michaelangelo sculpted David and DaVinci painted The Virgin of the Rocks. The Garden seems like a piece of modernist art miraculously created several centuries ahead of its time.

Consider: Did Bosch introduce the ‘Acoustic Age’ centuries before McLuhan’s 1974 lecture? (See my annotations here and here.)

Living in the Acoustic Age

My goal here isn’t to make my contribution to the volumes already written about the ability of these two men to see far ahead of their time. Regardless of how much I write on the subject, I’d like to deintellectualize and degamify this inquiry. In McLuhan’s words, I want to simply ‘do my thing’ under the ‘proscenium arch of satellites’. McLuhan explains these phrases in ‘Anesthesia’, the second chapter of From Cliche to Archetype.

Since Sputnik put the globe in a “proscenium arch,” and the global village has been transformed into a global theater, the result, quite literally, is the use of public space for “doing one’s thing.” A planet parenthesized by a man-made environment no longer offers any directions or goals to a nation or individual. The world itself has become a probe. “Snooping with intent to creep” or “casing everybody else’s joint” has become a major activity. As the main business of the world becomes espionage, secrecy becomes the basis of wealth, as with magic in a tribal society. Perhaps this is not the only [sic] latest form of cliche probe but merely the largest and most perceptible.

It is just when people all engaged in snooping on themselves and one another that they become anesthetized to the whole process. Tranquilizers and anesthetics, private and corporate, become the largest business in the world just as the world is attempting to maximize every form of alert. Sound-light shows, as new cliche, are in effect mergers, retrievers of the tribal condition. It is a state that has already overtaken private enterprise, as individual businesses form into massive conglomerates. As information itself becomes the largest business in the world, data banks know more about individual people than the people do themselves. The more the data banks record about each one of us, the less we exist.

Beyond Magical Substances

In strange and difficult times, my people like to imagine that, next year, we will reach ‘Jerusalem’, but translations of this metaphor into matter continue to inspire new scenes in the global theater of absurdity. These scenes don’t just unfold in geopolitics. For example, the second chapter concludes with a quote from a letter written by Sigmund Freud to his beloved Martha:

Woe to you, my Princess, when I come. I will kiss you quite red and feed you till you are plump. And if you are forward, you shall see who is the stronger, a gentle little girl who doesn’t eat enough or a big wild man who has cocaine in his body. In my last severe depression I took coca again and a small dose lifted me to the heights in a wonderful fashion. I am just now collecting the literature for a song of praise to this magical substance.

There you have it — another pursuit of a “magical substance”, another metaphor of liberation that collapses into absurdity. In the Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus wrote:

“It is the failing of certain literature to believe that life is tragic because it is wretched. Life can be magnificent and overwhelming – that is its whole tragedy. Without beauty, love, or danger, it would be almost easy to live.”

Some magical substances do “lift us to the heights in a wonderful fashion”, and for a time, we may feel that it’s almost easy to live. We may follow this feeling again and again and again, until we realize that we’re not really following our bliss. At that point, we may begin a search for alternatives to speaking as if stricken by some sort of amnesia.

Footnote

From Wikipedia: Assimil (often stylised as ASSiMiL) is a French company, founded by Alphonse Chérel in 1929. It creates and publishes foreign language courses, which began with their first book Anglais Sans Peine ("English Without Toil"). Since then, the company has expanded into numerous other languages and continues to publish today.

Excited to read your work, Lev!

A gardener has no language, so we chose his words for him.